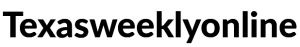

Pahalgam terror attack: Sketches of three terrorists released by security agencies

Security agencies have released sketches of three suspected terrorists believed to be involved in the brutal Pahalgam attack that claimed the lives of at least 28 tourists.

Pahalgam terror attack: NIA joins probe as Union Home Minister Amit Shah reviews security situation

Tuesday’s incident is considered one of the most serious attacks in Jammu and Kashmir since the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019. The government is yet to release an official count of casualties.

Terror with global audience: Was Pahalgam massacre timed for massive publicity, maximum diplomatic disruption?

Analysts believe, the attack carried out by The Resistance Front (TRF), was planned in a way that it gets huge publicity with the Vice President of the US visiting the country.

Videos capture deadly attack in Indian-administered Kashmir

[unable to retrieve full-text content] Shots can be heard on videos that captured the deadly attack on tourists in Indian-administered Kashmir

How Pope Francis redefined the Church’s ties with Africa

Thousands of miles from the Vatican, the death of Pope Francis is being mourned by millions of Catholics on the African continent. Francis, who was renowned for his liberal embrace of all groups of people and his vocal support for poor and marginalised communities, was a key figure on a continent sometimes referred to as the “future of the Catholic Church”, owing to the vast population of African Catholics: One in five Catholics is African. Throughout his papal leadership, Pope Francis solidified recently established Vatican conventions by visiting 10 African countries, reinforcing engagements made by his predecessors. Before the 1960s, popes hardly left the Vatican. Leaders across Africa, too, are mourning his death. Kenya’s President William Ruto referred to the late pope as someone who “exemplified servant leadership through his humility, his unwavering commitment to inclusivity and justice, and his deep compassion for the poor and the vulnerable”. Here’s how the late Pope Francis prioritised Africa during his tenure: A devotee reacts as residents and the faithful gather at N’Dolo Airport for a mass celebrated by Pope Francis, in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, February 1, 2023 [Luc Gnago/Reuters] Pope Francis’s many trips to Africa Pope Francis made five trips to Africa throughout his papacy, during which he visited 10 countries. Advertisement He opted to visit nations that were in strife and were facing war or low-level conflict. He also focused on those struggling with economic and climatic challenges. The pontiff did not shy away from holding mass in ghettos or kissing the feet of warring leaders in hopes of bringing peace. Those visits modelled those of Pope John Paul II (1980-2005), who visited more than 25 African countries in his 25 years of service, transforming the way the Vatican engaged with the continent. Pope Benedict XVI (2005-2013) visited three African countries over two visits. These are the countries Pope Francis visited and when: 2015: East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, Central African Republic – CAR) The pontiff’s six-day visit to three African countries in November 2015 was replete with colourful welcomes and huge mass events. In Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, the pope is still remembered and revered for holding mass in Kangemi, a low-income neighbourhood. There, he decried what he called “modern forms of colonialism” and pointed out that the country’s urban poor were excluded and underserved. He also criticised wealthy minorities who, he said, hoard resources meant for all. In a colourful welcome to Uganda, the pope enjoyed traditional dances from different ethnic groups. He blessed dozens of children thrust into his popemobile, the open-sided car, as he cruised through throngs of people gathered to catch a peep. He also visited a treatment centre for disabled children and spoke to more than 700 disabled people. A UN peacekeeping soldier patrols a street near Bangui’s Koudoukou mosque, Central African Republic, before the arrival of Pope Francis for a meeting with the Muslim community on November 30, 2015. CAR descended into civil war after rebel groups tried to overthrow then-President Francois Bozize in 2012 [Andrew Medichini/AP] Healing a fractured country Then, in the CAR, the pope did the unprecedented: He ventured into a Muslim neighbourhood amid religious tensions in the country that had lasted for months. Advertisement The PK5 neighbourhood in the capital, Bangui, had been off-limits to Christians before then, but as the pope made his way to a mosque there, crowds of Christians followed him in. People who had lost touch cried as they embraced each other. Pope Francis urged both sides to lay down their arms and called Africa “the continent of hope” in his speeches. The visit would eventually lead to a peace agreement between the warring factions, although true peace would take another five years. 2017-2019 North Africa (Egypt, Morocco) In April 2017, Pope Francis visited Cairo for two days to support the Coptic minority there, the largest Christian community in the Middle East. Coptic Christians have been subject to marginalisation and deadly attacks for years in Egypt. Francis also reached out to Muslim clerics in the country. On his March 2019 trip to Morocco at the invitation of King Mohammed VI, the pope also called for religious tolerance and inclusion. He urged Morocco to respect the rights of refugees and immigrants. Pope Francis steps off the plane as he arrives in Port Louis, Mauritius, from Madagascar, September 9, 2019 [Alessandra Tarantino/AP Photo] 2019 Indian Ocean (Mozambique, Madagascar, and Mauritius) The same year, in September, Pope Francis turned his attention to Southern Africa, particularly countries in the Indian Ocean. In Mozambique and Madagascar, he called for an end to poverty and better protection of the environment in a region where climate change has brought intensifying storms and destructive cyclones. A man holds flags next to the audience as they await the arrival of Pope Francis for a holy mass at the John Garang Mausoleum in Juba, South Sudan on February 5, 2023 [Ben Curtis/AP] 2023: Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and South Sudan Amid ongoing conflict and a humanitarian crisis brought on by armed factions looking to control the country, the pope’s visit to the DRC symbolically called for peace and reconciliation in the troubled central African nation. The DRC, which has the largest number of Catholics in Africa – an estimated 35 million people – was an important one for the pope, who’d had to postpone the trip because of ill health. Congolese showed up in the thousands to welcome him. Advertisement A show of humility for South Sudan In South Sudan, the pope called for continued peace between rivals President Salva Kiir and his deputy, Vice President Riek Machar. The country, Africa’s youngest, has been rocky since it gained independence from Sudan in 2011. Immediately after, and until 2013, a civil war broke out between factions loyal to the two leaders, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands and the displacement of millions of South Sudanese. Five years before he set foot in South Sudan, the pope had expressed an unusual

Kremlin critic decried for ‘racist’ rant on minorities fighting for Russia

Kyiv, Ukraine – Vladimir Kara-Murza barely survived two suspected poisonings in 2015 and 2017 that he claimed were orchestrated by the Kremlin. The bearded, balding 43-year-old may not be as outspoken as opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who nearly died of similar nerve agent poisoning in 2020. But Kara-Murza, a Cambridge-educated historian, has been instrumental in convincing Western governments to slap personal sanctions on dozens of Russian officials. In 2023, a Moscow court sentenced him to 25 years in jail for “treason” and while behind bars, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his columns for The Washington Post. Released last year as part of a prisoner swap, Kara-Murza settled in Germany and continued his advocacy work against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government and Moscow’s war in Ukraine. But last week, Kara-Murza’s remarks about the ethnic identity and alleged bloodthirst of Russian servicemen rattled many on both sides of Europe’s hottest armed conflict. “As it turns out, [ethnic] Russians find it psychologically difficult to kill Ukrainians,” Kara-Murza told the French Senate on Thursday while explaining why Russia’s Ministry of Defence enlists ethnic minorities. Advertisement “Because [ethnic Russians and Ukrainians] are the same, we’re similar people, we have an almost similar language, same religion, hundreds and hundreds of years of common history,” said Kara-Murza. Russians and Ukrainians are ethnic Slavs whose statehood dates back to Kyivan Rus, medieval Eastern Europe’s largest state torn apart by Mongols, Poles and Lithuanians. “But to someone who belongs to another culture, it is allegedly easier” to kill Ukrainians, Kara-Murza added. His remarks made observers and Indigenous rights advocates flinch and fume. A former Russian diplomat said “measuring the degree of one’s cruelty by their ethnicity is a dead end.” The Kremlin does not specifically “recruit minorities, they recruit people from the poorest regions, and those are, as a rule, ethnic autonomies”, Boris Bondarev, who quit his Ministry of Foreign Affairs job in protest against Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, told Al Jazeera. “Only a dull man could say that in the war’s fourth year in a multiethnic society,” said Indigenous peoples activist Dmitry Berezhkov, of the Itelmen nation on Russia’s Pacific peninsula of Kamchatka. Russian liberal opposition figures, mostly middle-class urbanites, “drown as soon as they tread on the thin ice” of ethnic minority issues, he added. Ethnic Russians constitute more than two-thirds of Russia’s population of 143 million. The rest are minorities – from millions of ethnic Ukrainians and Tatars to smaller Indigenous groups in Siberia and the Arctic that have regional autonomy, albeit mostly nominal. Advertisement Even in regions rich in hydrocarbons, rare earths or diamonds, the minorities live in rural, often inhospitable areas, co-existing and mingling with ethnic Russians. They all rely on Kremlin-funded television networks more than urban dwellers, often have no internet access and see the sign-up bonuses and salaries of servicemen fighting in Ukraine as a ticket out of the dire poverty their families live in. Recruits receive up to $50,000 when they sign up, and earn several thousand dollars a month – a fortune for anyone from those regions irrespective of their ethnic background. “This is colossal money for them, they will never earn it in their lives, no matter whether they are Buryat or Russian,” Bondarev said. In response to a squall of criticism, Kara-Murza wrote on Facebook on Monday that the accusations were mere “lies, manipulations and slander”. To Berezhkov, the comment further tainted Kara-Murza’s image. “In the past, [Kara-Murza’s words] could be seen as a mistake – but now, they are his position,” he said. To another minority rights advocate, Kara-Murza’s diatribe sounded like a “signal for future voters” in the post-war, liberal Russia that exiled Kremlin critics hope to return to. Oyumaa Dongak, who fled Tyva, a Turkic-speaking province that borders China, thinks Kara-Murza and other exiled Russian opposition leaders are “competing” with Putin. “It’s not him, it’s us who defend [ethnic] Russians,” she told Al Jazeera. In 2024, Kara-Murza said Western sanctions imposed on Moscow after the 2022 invasion are “unfair and counterproductive” and hurt Russians at large. He wanted the West to lift wider sanctions and instead target individual officials. Advertisement A Ukrainian observer said Kara-Murza does not want ethnic Russians who can potentially vote for now-exiled opposition leaders to feel collective guilt for the atrocities committed in Ukraine. “People don’t feel guilty. If you club them in the head with moral condemnation every day, people will not admit their guilt but will hate anyone who clubs them,” Kyiv-based analyst Vyacheslav Likhachyov told Al Jazeera. “That’s why the tales about the atrocities of Chechen executioners and Buryat rapists are and will be popular,” he said. Fighters deployed by Chechnya’s pro-Kremlin leader Ramzan Kadyrov were dubbed a “TikTok army” for staged videos of them “storming” Ukrainian strongholds. Their actual role in the war is mostly reduced to guarding occupied areas, terrifying and torturing ethnic Russian servicemen who refuse to fight. But Buryats, Buddhist natives of a scarcely populated and impoverished region near Mongolia, have become notorious in Ukraine in 2022. Human rights groups and Ukrainian officials identified personal details of some Buryat soldiers that tortured, raped and killed civilians in Bucha and other towns north of Kyiv. But as ethnic Buryats are hard to distinguish from other minority servicemen with distinctly Asian features, Ukrainians often label them all “Buryats”, a community activist said. “All Caucasus natives are seen as Chechens, and all Asians are considered Buryats,” Aleksandra Garmazhapova, who helps Buryat men escape mobilisation and flee abroad, told Al Jazeera. Advertisement However, the overwhelming majority of servicemen who committed alleged war crimes in Bucha were reportedly ethnic Russians. Garmazhapova survived because Ukrainian forces started shelling Russian positions, and his captors fled to a basement. “Slavs, Slavs, they were all Slavs,” Viktor, a Bucha resident who was doused with fuel by Russian servicemen who placed bets on how far he would run once they set him on fire, told Al Jazeera in 2022, just days after his ordeal. Adblock test (Why?)

Pahalgam terror attack: Terrorists asked Kanpur businessman’s name before shooting him in front of wife

Shubham was among the 26 persons, mostly tourists, who were killed at Baisaran near the resort town of Pahalgam in Anantnag district, in one of the most gruesome attacks targeting civilians in Kashmir in a long time.

US-based techie among victims of Pahalgam terror attack, Bengal CM assures support to grieving family

One of the deadliest terror attacks to rock J&K in recent years, 40-year-old Bitan Adhikary, a tech professional from Florida, US who was visiting India with his family, was among the several people brutally killed by terrorists in Pahalgam.

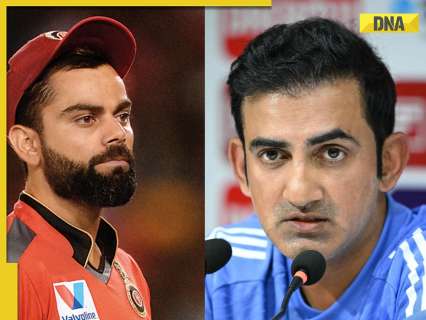

From Virat Kohli to Gautam Gambhir: Indian Cricket fraternity condemns terror attack in Jammu and Kashmir’s Pahalgam

Indian Cricket fraternity condemns terror attack in Jammu and Kashmir’s Pahalgam. From Virat Kohli to national team head coach Gautam Gambhir, expressed their sorrow and anguish over the terror attack on tourists in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir on Tuesday.

PM Modi’s plane, which used Pakistan airspace while flying to Jeddah, skips it while returning after Pahalgam terror attack

PM Modi returned to Delhi early on Wednesday morning, after the Pahalgam terror attack that left 26 people dead. PM Modi cut short his trip to Saudi Arabia following the terror attacks in Jammu and Kashmir.