Trump admin fires top US copyright official days after terminating Librarian of Congress

President Donald Trump’s administration fired the top copyright official in the U.S. – just days after terminating the Librarian of Congress. Shira Perlmutter was in charge of the U.S. Copyright Office, which is overseen by the Library of Congress, until she was abruptly fired on Saturday. The U.S. Copyright Office told Fox News Digital that Perlmutter received an email from the White House, stating, “your position as the Register of Copyrights and Director at the U.S. Copyright Office is terminated effective immediately.” Trump fired Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, who was the first woman and first African American to be Librarian of Congress, on Thursday. The termination was part of the administration’s ongoing purge of government officials who are perceived to be opposed to Trump and his agenda. DEMS ERUPT AFTER REPORT OF TRUMP FIRING LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS: ‘A DISGRACE’ The White House did not immediately respond to Fox News Digital’s requests for comment on the matter. Hayden tapped Perlmutter to lead the Copyright Office in October 2020. Like Perlmutter, Hayden was notified of her firing in an email, according to The Associated Press. NEW RESISTANCE BATTLING TRUMP’S SECOND TERM THROUGH ONSLAUGHT OF LAWSUITS TAKING AIM AT EXECUTIVE ORDERS “Carla,” the email from the White House’s Presidential Personnel Office reportedly began. “On behalf of President Donald J. Trump, I am writing to inform you that your position as the Librarian of Congress is terminated effective immediately. Thank you for your service.” Perlmutter’s office recently released a report examining whether artificial intelligence companies can use copyrighted materials to “train” their AI systems. CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS DOUBLES DOWN ON DEFENSE OF COURTS AS SCOTUS GEARS UP TO HEAR KEY TRUMP CASES The report followed a review that started in 2023 with opinions from thousands of individuals, including AI developers, actors and country singers. The Copyright Office clarified its approach in January, as one based on the “centrality of human creativity” in authoring a work that warrants copyright protections. The Copyright Office takes in about a half a million copyright applications each year, covering millions of creative works. “Where that creativity is expressed through the use of AI systems, it continues to enjoy protection,” Perlmutter said in January. “Extending protection to material whose expressive elements are determined by a machine… would undermine rather than further the constitutional goals of copyright.” Perlmutter, who holds a law degree, was previously a policy director at the Patent and Trademark Office and worked on copyright and other areas of intellectual property. She also previously worked at the Copyright Office in the late 1990s. The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Exploited, abused, trapped: The lives of Italy’s South Asian rose sellers

Names marked with an asterisk have been changed to protect identities. After a night of selling roses in Tuscany, Mohammed* was cycling along a seaside road when someone in a passing car hit him on the back with a pole. He fell to the ground. It was August 2013 and Mohammed was 22. He believes it was intentional and likely a racist attack. “I was already broken,” he said. “But after that, I was in pieces.” He suffered emotionally and still has back pain from the assault today. He had arrived in Italy a few months earlier following a harrowing seven-month journey via land and sea. He had no documents or money and owed 9,000 euros ($9,700) to the Bangladeshi agents who had arranged his trip. Mohammed says he was guided by multiple people along the way. When he arrived in Tuscany, he was approached by men from his country who, he says, put him to work selling roses in busy city centres so he could pay for room and board at a house with nine other foreign workers. “I didn’t like bothering people while they were eating to ask them if they wanted to buy a rose from me,” said Mohammed. “But I had no choice.” Street rose sellers in Italy work long hours and are often trapped in a vicious cycle of debt and despair [Agostino Petroni/Al Jazeera] Rose sellers are a common sight in Italy’s largest and most romantic cities, such as Rome, Milan or Turin. South Asian men wield bunches of red roses and approach hordes of tourists every night. During high season, you may see about 20 rose sellers a night spread across the city centre – and dozens more on Valentine’s Day weekend. But hidden behind the universal symbol of love is a bleak story of hardship, labour exploitation and human trafficking. On a given night, rose sellers of all ages can walk miles on end, weathering rejection, police scrutiny and even violence to sell a few flowers. “They are a pain in the ass,” said a Welsh tourist on a February night, at the top of the Spanish steps in Rome. Despite their familiar presence and the dangers they encounter, there are almost no official records or data about these street vendors. In recent years, several attacks on rose sellers in various parts of the country have been reported in local news outlets; they are often carried out by young Italian men. In November, a 50-year-old Bangladeshi rose seller described as a “well-known face” in Ivrea, Turin, was brutally beaten by a group of three men. Another Bangladeshi seller was randomly pushed into the Naviglio canal in Milan by two men in 2020. A year earlier, two young men in Nettuno reportedly beat and robbed a seller whose origin was unknown. It is unclear what consequences – if any – the perpetrators ultimately faced in each case. “They are visible to everybody but there is no data. There is nothing,” said Marina Mazzini, who conducted one of the only case studies on rose vendors in Italy for the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI). For this article, as well as Mohammed, Al Jazeera interviewed two other rose sellers, three former vendors and four NGOs who have supported dozens of rose vendors with their documentation. Fear, uncertainty and thankless work South Asians who end up selling roses in Italy are predominantly from Bangladesh. Nearly all have crippling debts and rely on members of their communities to help them start life in a new country. Mohammed says he was hosted in Tuscany by a man of Bangladeshi origin and another from Pakistan. On the first day Mohammed was to sell roses, his hosts gave him 30 euros ($32) and told him to go to a local flower vendor to buy them. The hosts were always in contact with the flower shops to track how many roses each seller bought, Mohammed said. He says he spent at least 12 hours a night traversing the city’s restaurants, bars, monuments and other tourist hot spots until all the flowers were sold before returning to his hosts’ home, where he would sleep with five others in the same room. A rose vendor makes a sale in Fontana di Trevi, one of Rome’s busiest tourist destinations [Agostino Petroni/Al Jazeera] There is no going rate for a red rose. Vendors may ask for a few euros and accept between two and five ($2.16 to $5.40) depending on each sale. If he made 120 euros ($129) from selling 200 roses on a good night, he would have to give 60 euros ($65) to the flower seller and 50 euros ($54) back to his hosts for room, board and the promise of a good lawyer to get his paperwork in order, Mohammed said. The 10 euros ($11) left were usually spent on cigarettes and a coffee. Soon, he had trouble sleeping, and started suffering from panic attacks and nightmares about his journey – part of which he says was spent on a ship with 200 other people making their way from Egypt to Sicily. If local police poked around when he was working, Mohammed was transferred to a different area. In between selling flowers, he worked at a Bangladeshi grocery store in Genova, where he says his work was never compensated, sold artichokes at a Milan market and sold roses again in southern Italy, while toiling intermittently as a gardener, dishwasher and chef’s assistant. After about seven years, Mohammed was granted asylum in 2018 as a victim of human trafficking with the help of a local NGO, Comunità Progetto Sud. Mohammed believes his countrymen let him down. “A Moroccan helped me to learn Italian and Italians helped me get documents,” Mohammed said. “I have only been exploited by my own people.” “To the young people who are now coming to Italy, I tell them not to trust their own people,” he added. Recognising exploitation Uddin Md Mofiz, 55, who

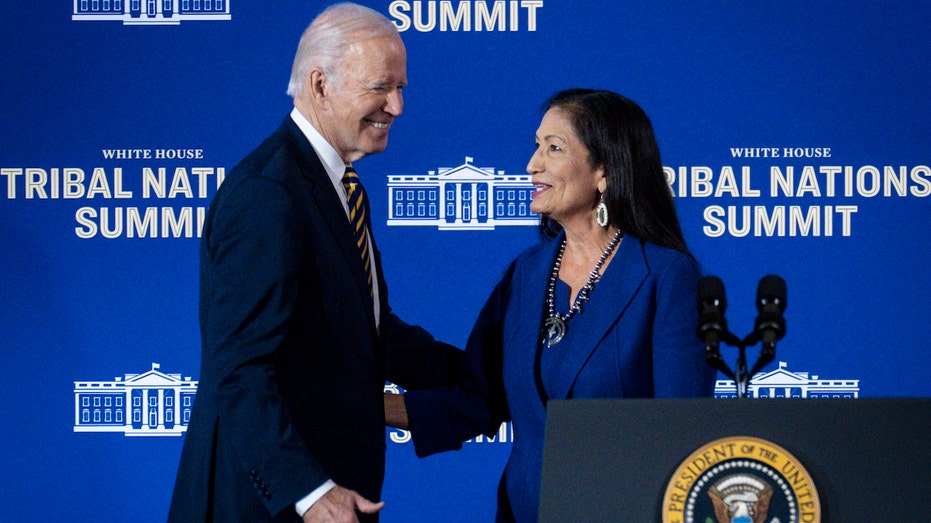

Biden admin poised to green-light tribal gambling expansion despite opposition from Native Americans, Dems

The Biden administration is poised to move forward with a plan to allow a tribe in the Pacific Northwest to build a second casino far beyond its territory, a move other tribes and Democrats in the region have argued vehemently against. The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) is expected to issue a final environmental impact statement (EIS) potentially green-lighting the Oregon-based Coquille Indian Tribe’s proposal to develop and operate a casino outside its territory in Medford, Oregon, as soon as this week, people familiar with the federal review process told Fox News Digital. The BIA issued its draft EIS in November 2022 for the proposal and the public comment period for that action lasted until late February. A wide range of voices, including several regional tribes, tribes nationwide and bipartisan lawmakers, blasted the draft EIS which recommended the federal government approve Coquille’s move to build an off-reservation casino, the so-called Cedars at Bears Creek. “The Coquille Indian Tribe’s application to transfer fee land in Medford, Oregon into trust for gaming using the restored lands exception directly threatens the sovereign rights of tribal governments to operate gaming on their lands,” the Tribal Alliance of Sovereign Indian Nations, which represents 13 tribes in California, wrote to BIA Assistant Secretary Bryan Newland earlier this month. NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBE PLANS PROTESTS, CONSIDERS SUING BIDEN ADMIN OVER OIL-LEASING CRACKDOWN In a similar letter to Newland, the California Nations Indian Gaming Association, which represents dozens more federally-recognized tribal governments on issues related to gaming, similarly argued that finalizing the draft EIS would threaten its members’ “sovereign rights” as tribes. The issue over whether to approve the Coquille’s casino has been hotly-contested since the tribe first proposed the plan about a decade ago. The plan was proposed under an Obama administration policy that eased gaming and trust-land acquisition restrictions, an action that critics have worried the Biden administration is doubling down on. BIDEN TOUTS PRO-NATIVE AMERICAN EFFORTS DESPITE AXING OIL DRILLING THAT SUSTAINS TRIBES But opponents of the Cedars at Bear Creek proposal — including the California Nations Indian Gaming Association, Tribal Alliance of Sovereign Indian Nations, other tribes and lawmakers — have particularly argued that developing the project would infringe upon other nearby tribes’ rights and have the impact of lowering their gaming revenue. They have also said the move would set a dangerous precedent whereby tribes are able to freely build gaming venues on or near other tribes’ lands and reap the financial benefits. The Coquille already operate the Mill Casino in North Bend, Oregon, and the Cedars at Bear Creek casino would be the first off-reservation casino in Oregon. “The bottom line is if the Coquille Tribe is allowed to build another casino in Oregon, it will likely lead to allout gaming conflicts between Oregon and California tribes,” Democratic Oregon Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, and Democratic Sen. Alex Padilla of California wrote last year to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. “It would also have a detrimental impact on tribes in Oregon and California that rely on the income generated by their gaming facilities and utilize those funds to provide vital governmental services,” they continued. “This would have negative consequences in many of our communities if Oregon and California’s carefully crafted balance between producing gambling revenues and an overall focus of public good for our citizens were seriously compromised by the Department of Interior approving a second casino for the Coquille Tribe.” NATIVE AMERICAN LEADERS REBUKE BIDEN ADMIN OVER OIL LEASING BAN: ‘UNDERMINES OUR SOVEREIGNTY’ Democratic Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek and Reps. Suzanne Bonamici, D-Ore., Earl Blumenauer, D-Ore., Jared Huffman, D-Calif., Cliff Bentz, R- Ore., and Doug LaMalfa, R-Calif., have also opposed the new Cedars at Bear Creek casino. In addition, a broad coalition of tribes in the region led by the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, whose territory is near the site of the proposed casino, and including the Karuk, Tolowa Dee-Ní, Smith River and Klamath Tribes, have appealed to the federal government to reject the proposal. The Cow Creek have noted Coquille’s own estimates that show Cow Creek’s Seven Feathers Casino Resort would suffer a 25% decrease in gaming revenue if Cedars at Bear Creek is constructed. “I want to emphasize the profound impact Coquille’s second casino would have on my Tribe and my people,” Cow Creek Chair Carla Keene said during a BIA-hosted public hearing late last year. “It will impact essential governmental services that the Tribe provides. It will impact our education program. It will impact our ability to provide healthcare and social services that many of our members rely upon.” “If approved, and the doors open, this will open the floodgates for additional casinos in the State by this one Tribe,” added Cow Creek CEO Michael Rondeau. “The other Tribes do not enjoy that ability to open second casinos. The casino is 150 miles from their reservation.” Stephen Dow Beckham, an expert of Native American history and the Pamplin Chair of History at Oregon State University’s Lewis & Clark College, said during a second public hearing in January 2023 that the proposal was “wrongheaded.” NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBES DEPENDENT ON FOSSIL FUEL RESOURCES RIP BIDEN ADMIN FOR DOUBLE STANDARD “Never have I seen a case of more blatant, glaring reservation-shopping than the proposal of the Coquille Tribe to reach 168 miles from North Bend, Oregon into the treaty cession area of the Rogue River tribes to try to justify a second casino and entertainment venue,” Beckham remarked at the time. “The Coquille Tribe was not an aboriginal tribe in the Rogue River Valley. It lived over on the coast of Oregon. This project will have deleterious impacts on neighboring tribes,” he continued. “The impacts of the Coquille casino will undermine the delivery of services to the Karuk, the Klamath, the Tolowa, the Smith River and the Cow Creek peoples; all so that another tribe from North Bend, Oregon can have a second casino and hotel.” And last week, Russell Attebery, the chair